Table of Contents

Introduction

Benchmarks are central to the work we do at Puget Systems. They help us understand how new hardware behaves, compare components across generations, and ultimately make informed recommendations for our customers. When it comes to rendering specifically, benchmark scores often play a major role in workstation decisions. But a common question we hear from artists is: “Do these benchmark scores actually reflect how long my scenes will take to render?”

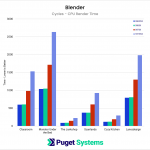

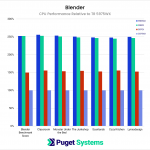

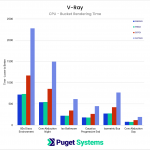

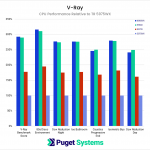

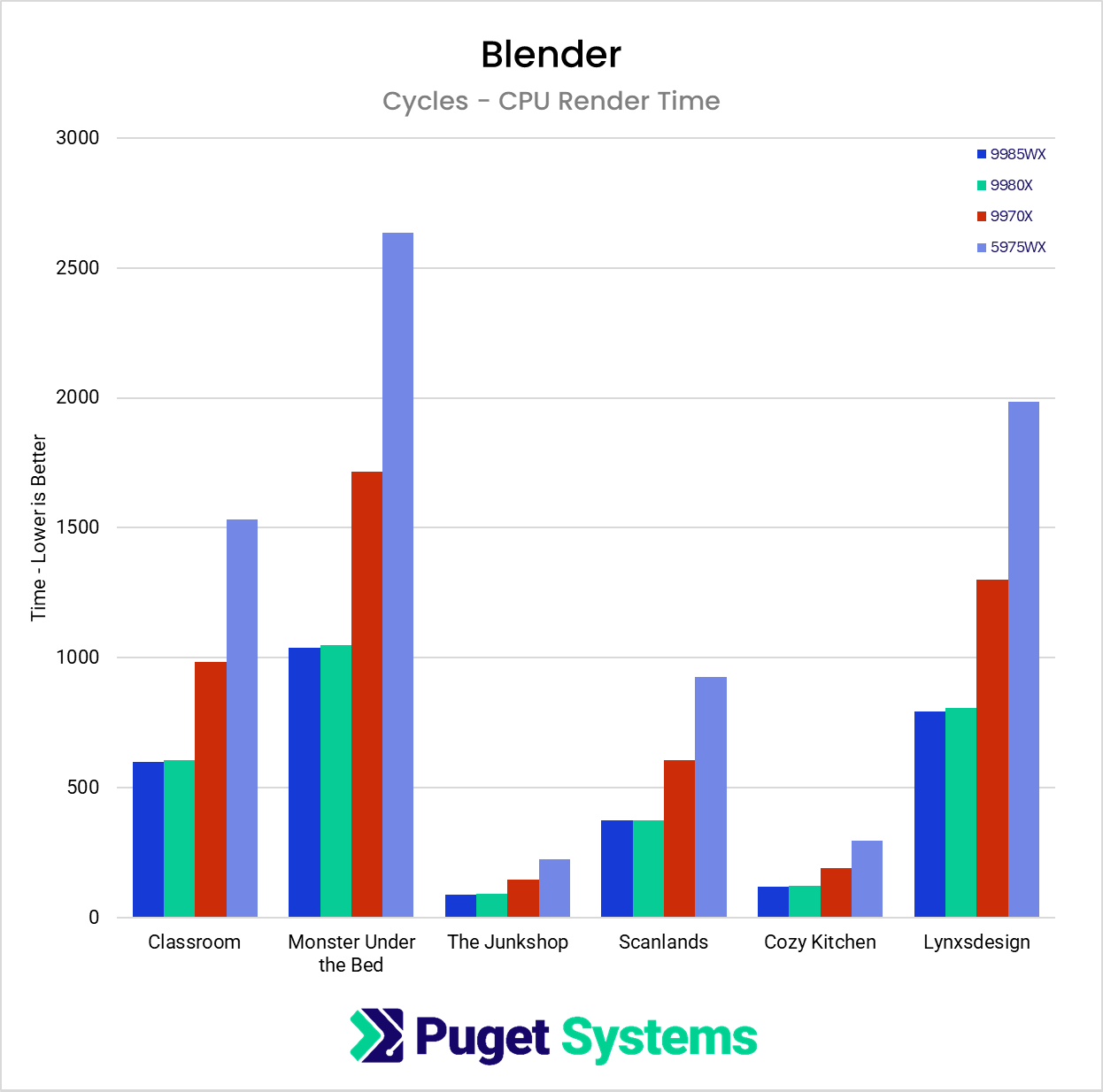

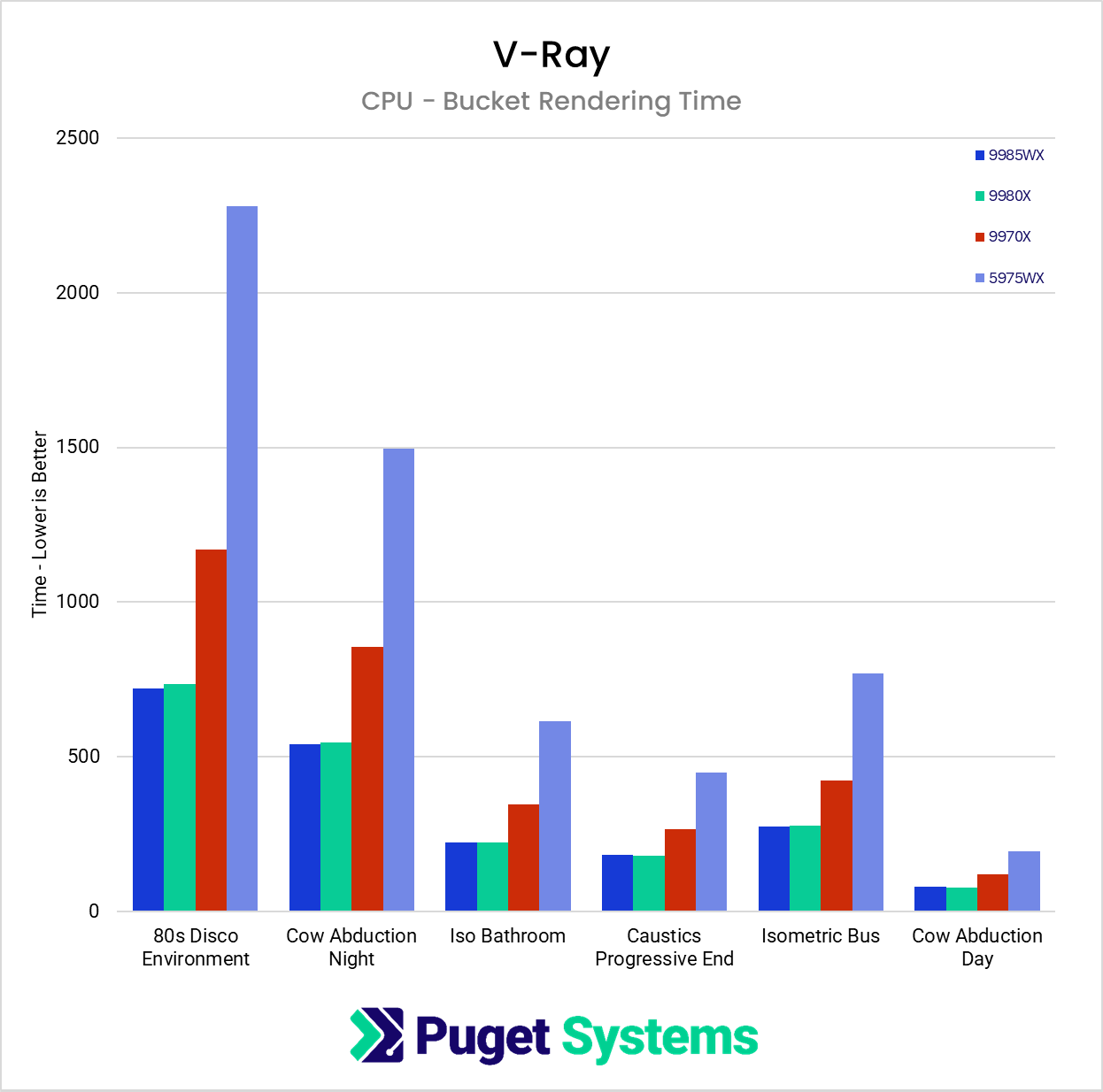

To explore that, we conducted a targeted study using both Blender (Cycles) and V-Ray. Instead of relying on a single standardized workload, we selected six real project scenes per application—each with different geometry, textures, sampling strategies, and features. Our goal was to see how closely the benchmark results aligned with real-world render times and whether certain types of scenes behaved differently than the benchmarks would predict.

Test Setup

To evaluate how well rendering benchmarks reflect real project performance, we created a controlled test environment using both Blender and V-Ray. Our goal was to compare standardized benchmark expectations with a set of diverse, real-world scenes that artists are likely to encounter.

Software and Render Engines

All tests were performed using the latest versions of Blender and V-Ray available at the time of testing. In Blender, we focused exclusively on the Cycles render engine. EEVEE was intentionally excluded because its real-time rendering approach does not align with the path-traced workloads used in benchmark tools.

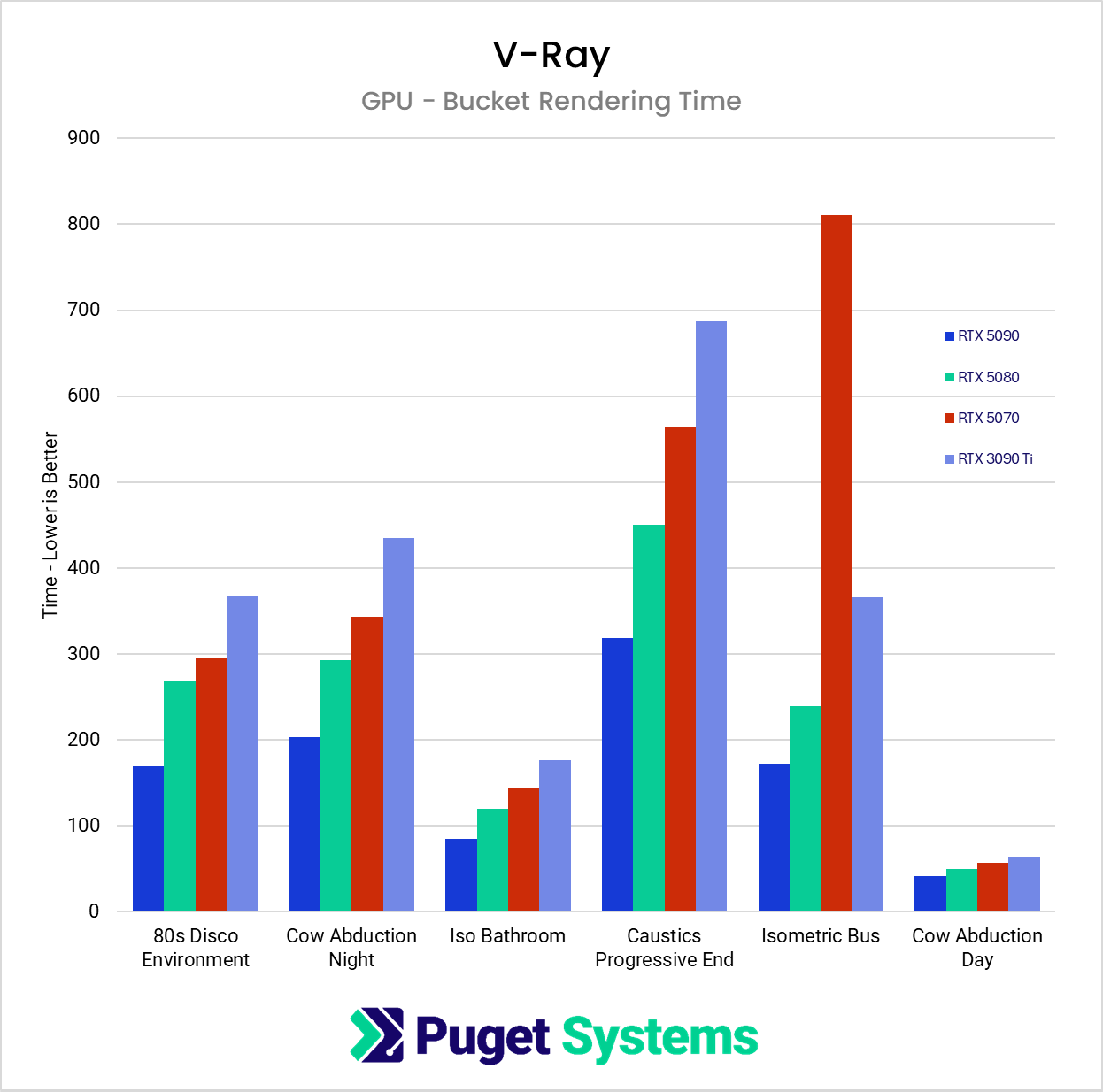

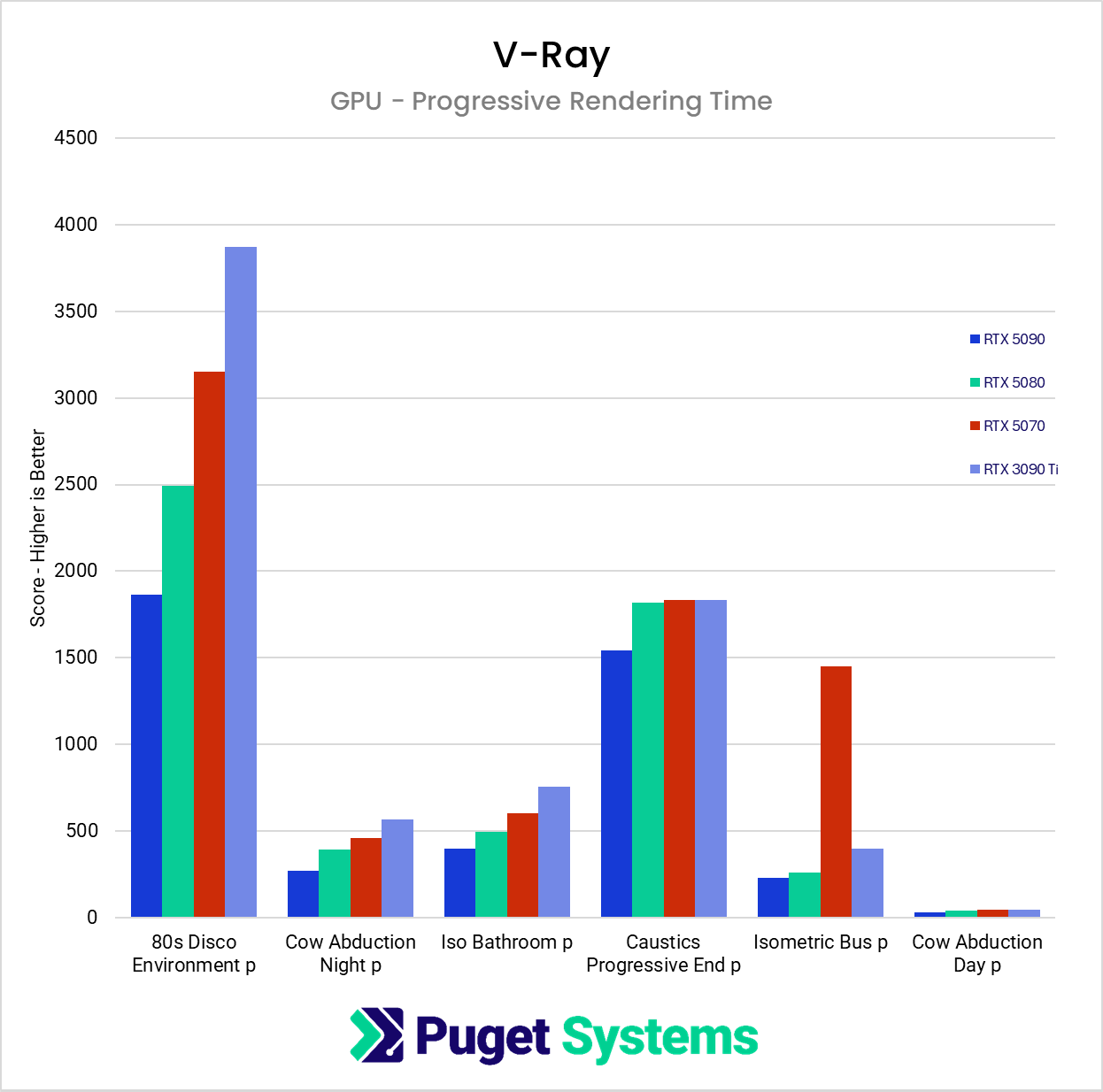

For V-Ray, CPU renders were performed with bucket mode, which is the standard for CPU-based production rendering. GPU renders were tested in both bucket mode and progressive mode in order to capture a wider range of behavior. Progressive rendering can alter how performance scales, especially in combination with AI denoisers, although all denoisers were disabled for this study.

Scenes

Each render engine was tested with six publicly available scenes. These projects were selected to represent a variety of complexities, including different geometry types, texture sets, lighting conditions, and sampling strategies. Render resolution was adjusted per scene so that total render times covered a broad range. This allowed us to observe whether short renders and long renders scaled differently across hardware. The Blender scenes are available here, and the V-Ray scenes are available on V-Ray scenes are available on their website.

Hardware

Tests were conducted on the following GPUs:

| GPU Model | CUDA Cores | RT Cores | Base Clock | VRAM | Memory Bandwidth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVIDIA GeForce RTX™ 5090 | 21760 | 170 | 2017 MHz | 32 GB | 1.79 TB/s |

| NVIDIA GeForce RTX™ 5080 | 10752 | 84 | 2295 MHz | 16 GB | 960 GB/s |

| NVIDIA GeForce RTX™ 5070 | 6144 | 48 | 2325 MHz | 12 GB | 672 GB/s |

| NVIDIA GeForce RTX™ 3090 Ti | 10752 | 84 | 1560 MHz | 24 GB | 1.01 TB/s |

For CPU based rendering, we used the following processors:

| CPU Model | Cores | Threads | L3 Cache | Base Clock | Boost Clock | TDP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMD Threadripper™ PRO 9985WX | 64 | 128 | 256 MB | 3.2 GHz | 5.4 GHz | 350 W |

| AMD Threadripper™ 9980X | 64 | 128 | 256 MB | 3.2 GHz | 5.4 GHz | 350 W |

| AMD Threadripper™ 9970X | 32 | 64 | 128 MB | 4.0 GHZ | 5.4 GHZ | 350 W |

| AMD Threadripper™ Pro 5975WX | 32 | 64 | 128MB | 3.6 GHz | 4.5 GHZ | 280W |

All GPU tests were run in the same workstation, using the Threadripper 9970X, to eliminate platform differences. Denoisers were disabled in every test to ensure that only raw rendering performance was measured.

Do Benchmarks Predict Render Performance?

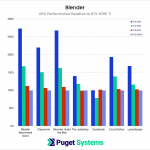

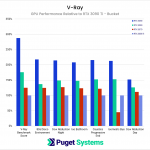

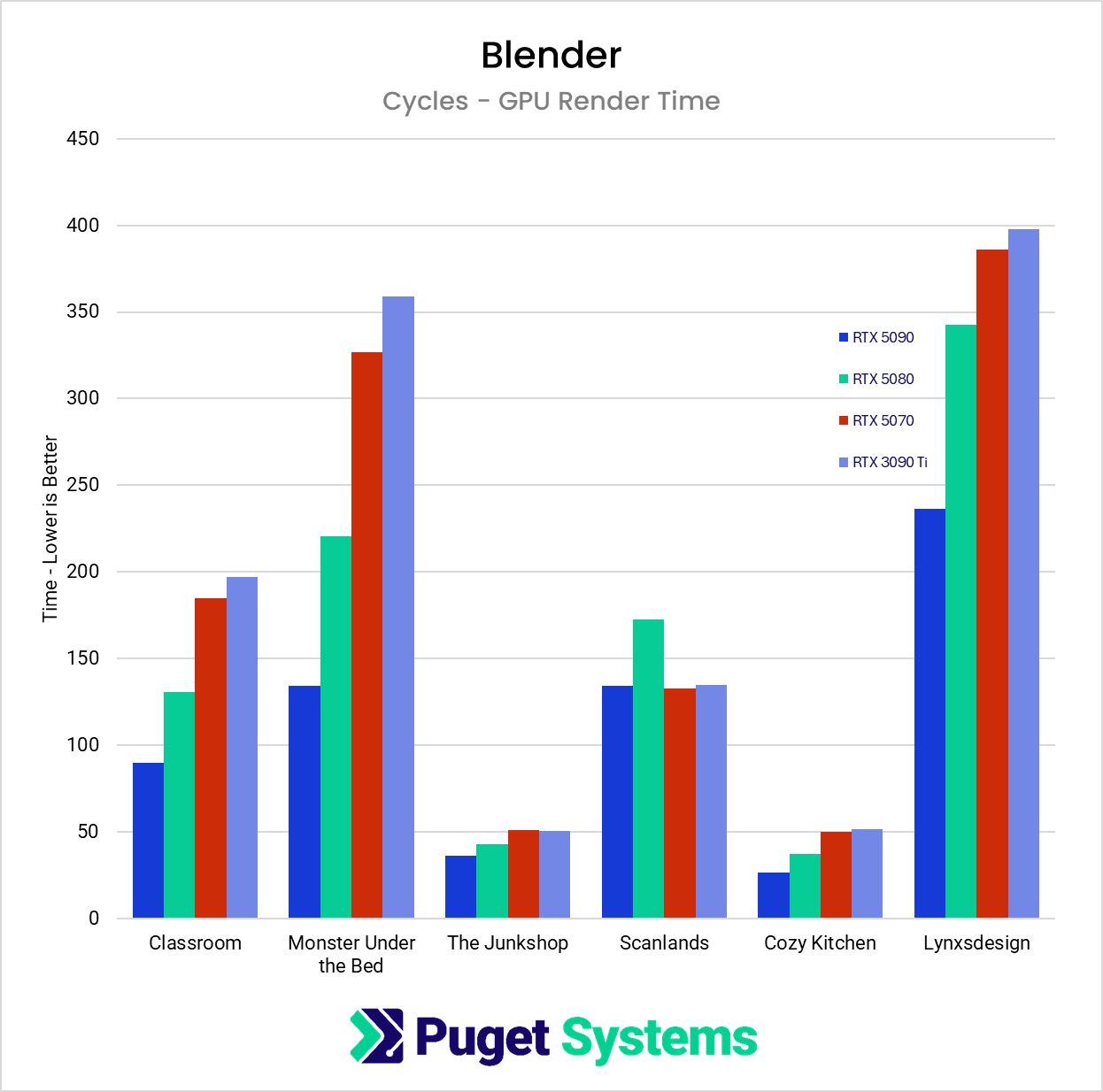

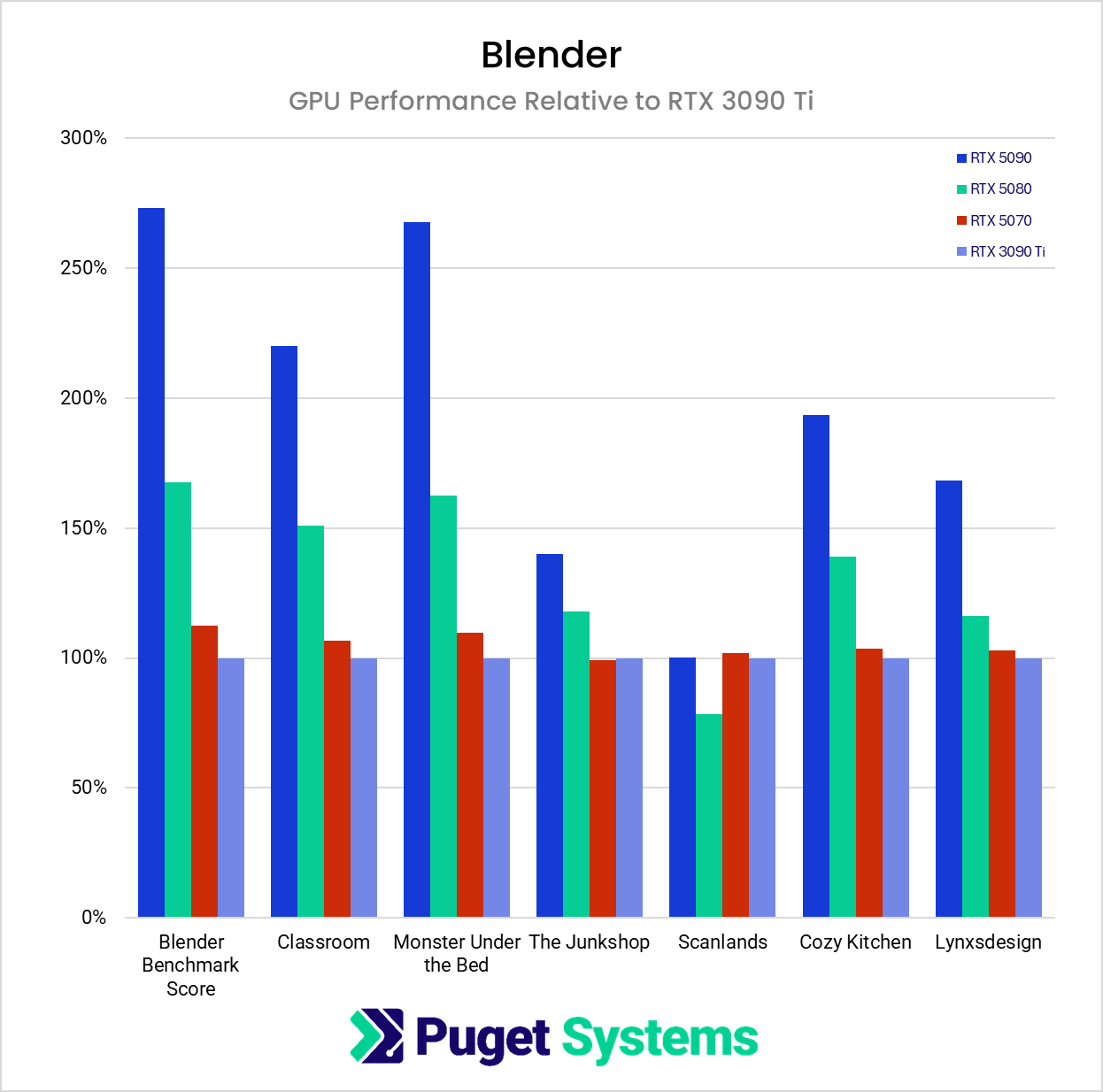

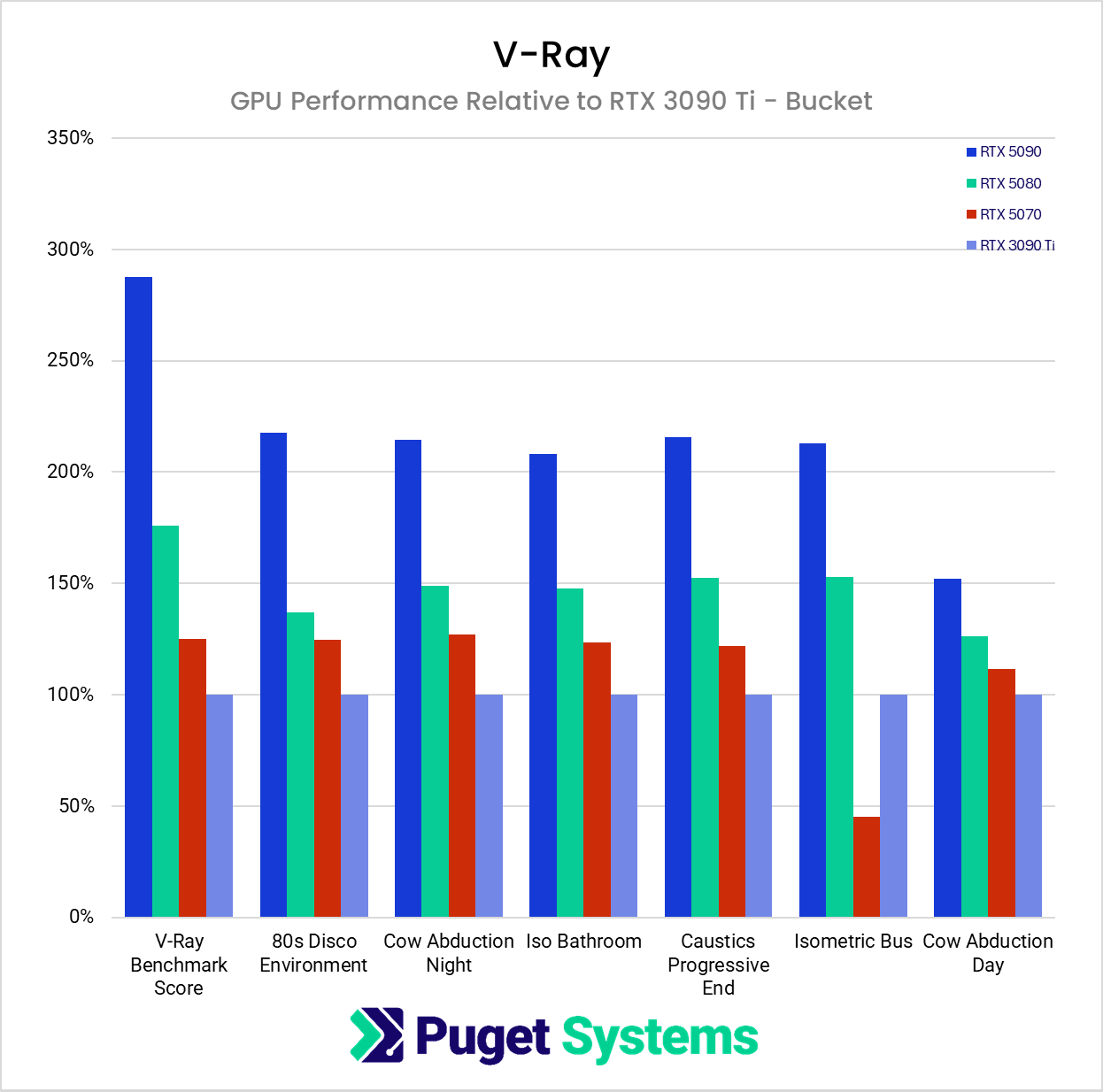

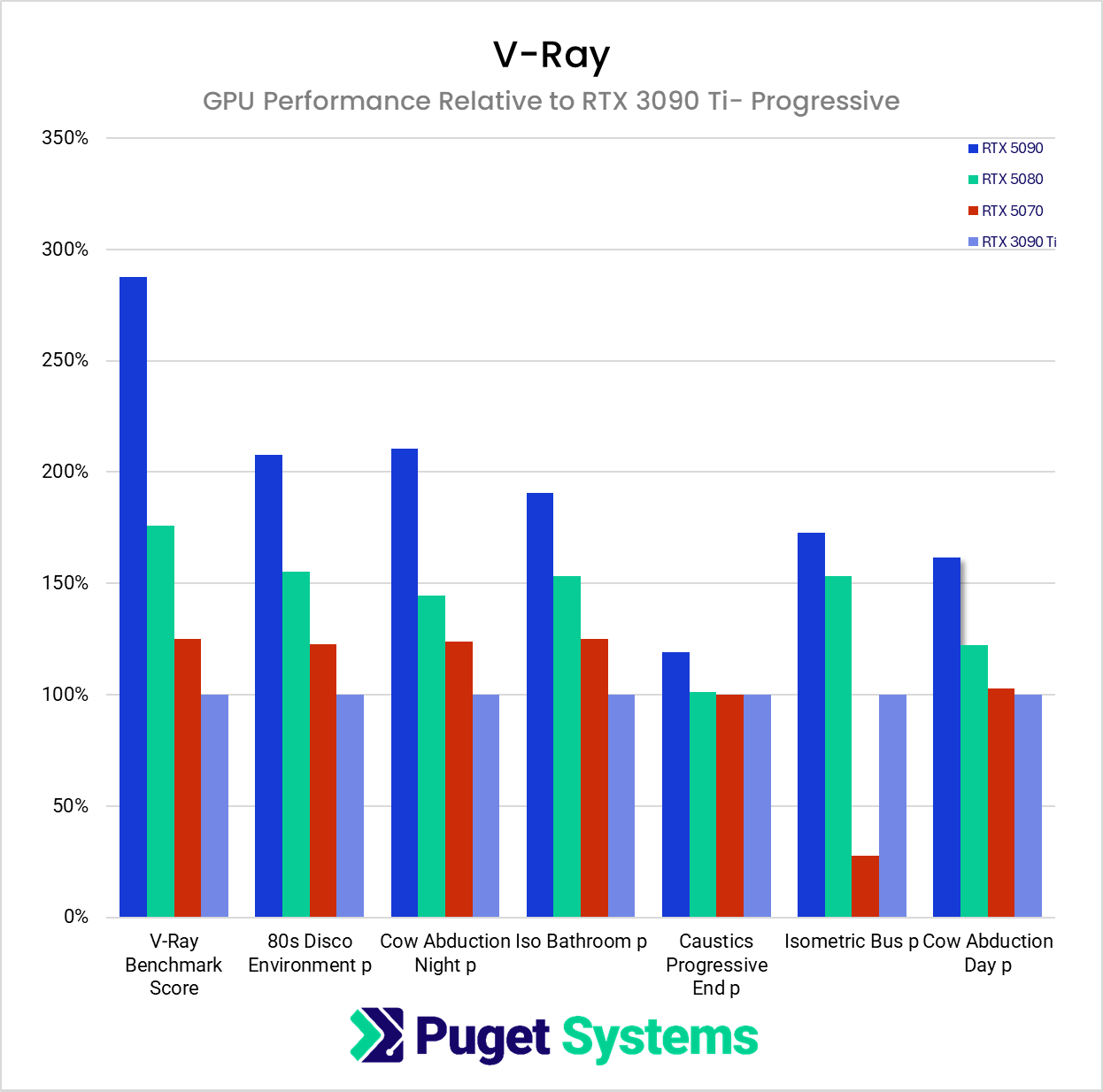

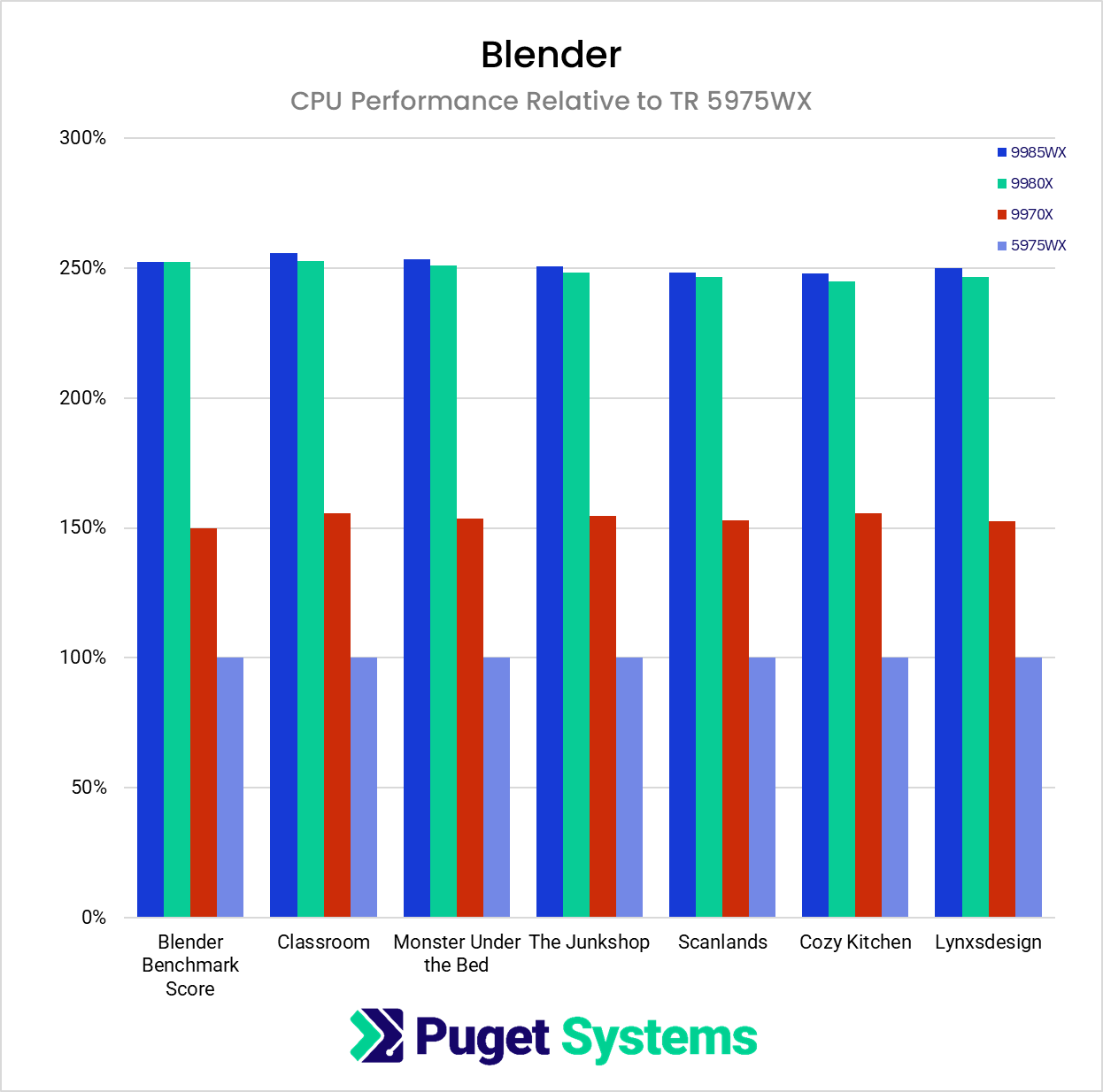

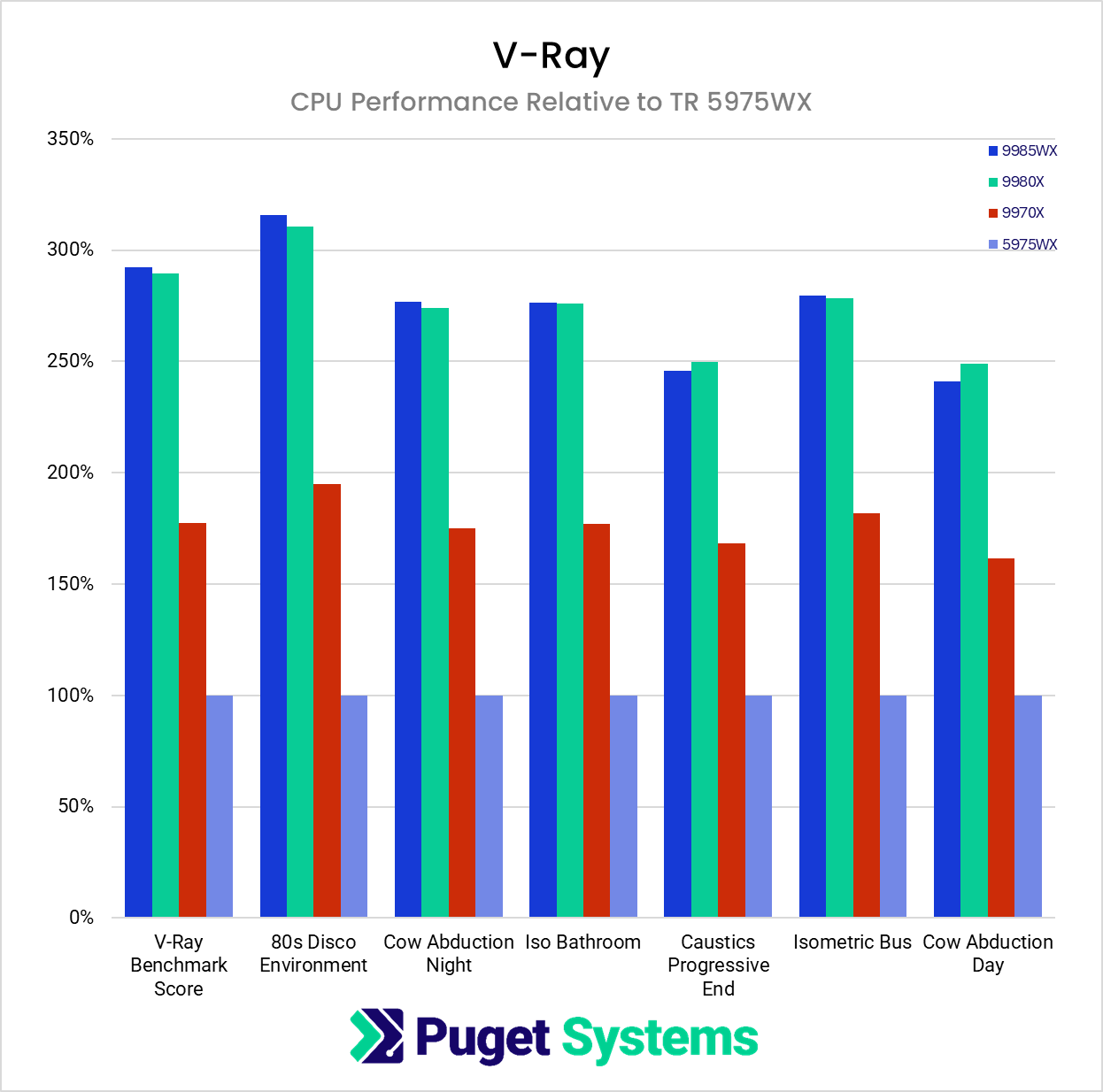

Across the twelve real scenes we tested, most behaved close to what the Blender and V-Ray benchmarks would predict. This is easiest to see in the Relative Performance charts below, where both benchmark scores and real-world render times are shown as a percentage relative to the RTX 3090 Ti (for GPUs) or TR PRO 5975WX (for CPUs) results. In the majority of cases, while the relative ranking between GPUs and CPUs did not exactly match the benchmark results, the scaling was at least in the ballpark.

GPU Results

One major exception on the GPU side occurred in the V-Ray “Caustics Progressive” project. While using bucket rendering, the preferred method to save on VRAM, it consumed just shy of 18GB. This caused the RTX 5070, which only has 12GB, to fall significantly behind. In progressive rendering mode, it consumed over 24GB – so only the RTX 5090 hand enough memory, although even it didn’t perform particularly well. Once the scene exceeded the available VRAM, the renderer was forced to pull data from system memory instead. This resulted in renders taking roughly three times longer than what the benchmark results would suggest for affected GPUs. This type of memory pressure does not appear in standardized benchmark tests, which are designed to run safely across a wide range of hardware and avoid memory-related failures.

Scenes with short render times, such as Blender’s Junkshop and Cozy Kitchen, as well as V-Ray’s Cow Obduction Daytime, did not scale as well as longer scenes. This is because every rendered frame has a certain amount of setup and other subtasks before the ray calculations begin. Artists with these sorts of projects might not find much value in moving to higher-end cards.

It should also be noted that the Blender Scanlands scene never exceeded 10GB of VRAM and utilized the GPU at 100% capacity; however, all four GPUs had nearly identical times across multiple runs. We could not explain these results.

CPU Results

On the CPU side, correlation with benchmark scores was even stronger. Renders across all CPU-based scenes followed the expected ranking with very little deviation, especially in Blender. We also compared a 64-core Threadripper against a 64-core Threadripper PRO of the same generation in order to evaluate the impact of additional memory channels. In our controlled tests, both processors produced almost identical render performance. However, we have observed a customer-supplied scene in the past that showed roughly a 10% difference between the two platforms. We have not been able to determine why that particular project was sensitive to memory channel count, but it serves as a reminder that certain scenes can behave differently based on memory architecture; users with very large datasets or memory-heavy effects may want to keep that in mind.

Overall, the results show that benchmarks provide a reliable baseline for raw performance, but unique project characteristics such as VRAM footprint or memory channel sensitivity can produce results that differ from the benchmark expectations.

Other Factors to Consider

While we have demonstrated that standardized rendering benchmarks are helpful for understanding raw performance, there are several real-world variables that fall outside the scope of both the benchmark workloads and our own controlled tests. These factors can significantly influence render times in production environments and are worth considering when evaluating hardware.

VRAM Usage

GPU rendering performance is heavily tied to available VRAM. When a scene fits comfortably within the memory on a graphics card, performance generally aligns with benchmark expectations. However, once a project exceeds the available VRAM, the renderer must rely on system memory to supplement it. This results in a substantial slowdown, sometimes several times slower than the benchmark scores would predict. Benchmarks rarely push VRAM to its limits because they are designed to run safely across a wide range of systems, which means they do not capture the behavior of scenes that approach or exceed memory capacity. Artists working with large textures, heavy displacement, or complex effects should be aware that VRAM is often the limiting factor in real projects.

AI Denoisers

Another important factor not captured in most benchmark workloads is the growing use of AI denoisers. Today, two primary options are widely used:

- Intel Open Image Denoiser, which runs on the CPU

- NVIDIA OptiX Denoiser, which runs on the GPU

Both can be applied regardless of whether the scene itself is rendered on the CPU or the GPU. This creates situations where a GPU render may rely on a CPU-based denoiser, or a CPU render may depend on a GPU-based denoiser. Either combination can alter performance in ways not reflected in benchmark scores.

Denoising can also represent a significant portion of total render time, especially with higher sample counts or complex lighting. The impact becomes even more dramatic when using Progressive Rendering. In this mode, the engine performs multiple passes until the number of samples are achieved. Denoisers are applied after each pass, which can lead to significantly longer overall render times than expected. Since our testing focused on raw rendering performance with denoisers disabled, these real-world costs were not part of the data presented here. Users who rely heavily on denoising should take this into account, particularly when choosing between CPU dominant and GPU dominant workflows.

Conclusion

Our testing showed that Blender and V-Ray benchmark scores generally align well with real-world render performance, especially in scenes that fit comfortably within GPU memory and use common rendering features. Both CPU- and GPU-based renders followed the expected performance patterns in nearly all of our test cases, and the benchmarks provided a reliable baseline for comparing hardware across generations.

However, our testing also highlighted important limitations that benchmarks do not reflect. Scenes that exceed GPU memory can render several times slower than expected, and denoisers can add significant overhead that does not appear in standardized tests. Certain projects may even respond differently to system architecture choices such as memory channel count.

For most artists, benchmarks remain a valuable tool, but they should not be the only factor in hardware selection. Understanding the memory requirements, complexity, and denoising strategies of your own projects is crucial. When benchmarks are interpreted in the context of actual workflow needs, users can make more accurate and confident decisions about the hardware that will best support their rendering pipelines.