Table of Contents

Introduction

PIX4Dmatic, by Pix4D, is a premier professional photogrammetry application that runs on both PC and Mac. For those unfamiliar with photogrammetry, the overall workflow is fairly straightforward. Images are taken, usually with a drone, and then the program automatically stitches them together and creates detailed 2D and 3D models based on them. In this article, we will be exploring how modern PC hardware affects performance in PIX4Dmatic, both on the component and system configuration levels.

Within PIX4Dmatic, there are a lot of options on how to generate models, which can have large effects on the accuracy of the end product and the time it takes to process the images. Scope can also vary from hundreds of relatively small images to tens of thousands of high-megapixel images. Processing time can thus swing dramatically, from minutes to hours or even days. We have found that the majority of time spent working on datasets in PIX4Dmatic is essentially “dead” time: time spent waiting for processing to occur, not requiring active user attention. On very small image sets, it may take longer to mark GCPs or verify the accuracy of results—but even at 100 images, we found that processing could take more than 10 minutes on top-end hardware.

The specific workflow we tested was processing two sets of aerial imagery taken by eBee X drones. After importing the images, which we did not measure, we performed the initial mandatory steps of calibrating the images and generating a dense point cloud. These steps are necessary for any deliverable from PIX4Dmatic. Then we generated a DSM and Orthomosaic, as well as a mesh. Finally, we exported the mesh to a .laz file. We have found that the first two steps generally took 30-50% of the total time for this process, with generating a mesh taking another 30-50%.

Test Setup

For this article, we tested with two datasets of different sizes. The first, smaller dataset is available on Pix4D’s website (“Urban area”) and consists of 100 images, while the latter comes directly from Pix4D and contains 1880 images. All these images were taken by a senseFly AeriaX camera. We are planning to test with an even larger dataset from a newer camera in the future.

We didn’t adjust any options within PIX4Dmatic for this testing, so all of the images were processed using default settings. This provides a solid baseline for performance, but there are a variety of preferences and content settings that could affect system performance. GPU acceleration is enabled by default.

We ran these tests across a variety of systems. For our CPU testing, we used an NVIDIA GeForce RTX™ 5080, and for our GPU testing, an AMD Threadripper™ 9970X. We followed our standard process here, and all the drivers, Windows versions, and BIOSs were up to date. Overclocking features were disabled, and RAM was run at the maximum JEDEC-supported speeds of each platform.

System Specifications (Expandable)

Top-End Ryzen Desktop

| AMD Ryzen™ 9 9950X3D |

| 64 GB DDR5-5600 (2 x 32 GB) |

| NVIDIA GeForce RTX 5080 |

Top-End Intel Core

| Intel Core™ Ultra 9 285K |

| 48 GB DDR5-6400 (2 x 24 GB) |

| NVIDIA GeForce RTX 5080 |

Mid-Tier Threadripper

| AMD Ryzen Threadripper 9970X |

| 128 GB Kingston DDR5-6400 ECC (4 x 32 GB) |

| NVIDIA GeForce RTX 5080 |

Mid-Tier Xeon

| Intel Xeon® w7-3565X |

| 128 GB DDR5-4800 ECC (8 x 16 GB) |

| NVIDIA GeForce RTX 5080 |

Mid-Tier Threadripper PRO

| AMD Ryzen Threadripper PRO 9975WX |

| 128 GB Kingston DDR5-6400 ECC (8 x 16 GB) |

| NVIDIA GeForce RTX 5080 |

Top-End Threadripper PRO

| AMD Ryzen Threadripper PRO 9995WX |

| 128 GB Kingston DDR5-6400 ECC (8 x 16 GB) |

| NVIDIA GeForce RTX 5080 |

Two-Gen Old Intel Core

| Intel Core i9 13900K |

| 64 GB DDR5-5200 (4 x 16 GB) |

| NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080 |

Mid-Tier Intel Core

| Intel Core Ultra 7 265K |

| 48 GB DDR5-6400 (2 x 24 GB) |

| NVIDIA GeForce RTX 5070 |

Top-End Laptop

| Puget Mobile 16″ |

| Intel Core Ultra 9 275HX |

| 64 GB DDR5-5600 (2 x 32 GB) |

| NVIDIA GeForce RTX 5090M |

Apple MacBook Pro (M3 Max)

| Apple 16″ MacBook Pro |

| Apple M3 Max 16-core |

| 64 GB Unified Memory (400 GB/s) |

| 40-core GPU |

GPU Test Platform

GPU testing was performed on the Mid-Tier Threadripper system with FE cards unless otherwise stated.

- NVIDIA GeForce RTX 5090

- NVIDIA GeForce RTX 5080

- MSI GeForce RTX 5060

- NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090

- NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 Ti

Raw Results

In our analysis, we found that the specific sub-steps of our benchmark (corresponding primarily to the different exports, e.g., Orthomosaic) did not show strong dependence on a given piece of hardware. There are some outliers to this—for example, generating DSM primarily scales with the CPU—but we found the overall time was a sufficiently good proxy for the totality of the workflow. However, for end-users who primarily make use of specific steps or exports, we know that having all of the results can be useful. To that end, we have reproduced all of our cleaned-up results in the table below.

For the rest of the charts, we converted from seconds to minutes or hours as appropriate. This kept numbers more readable, and while it does mean some precision was lost to rounding we don’t believe that alters our conclusions.

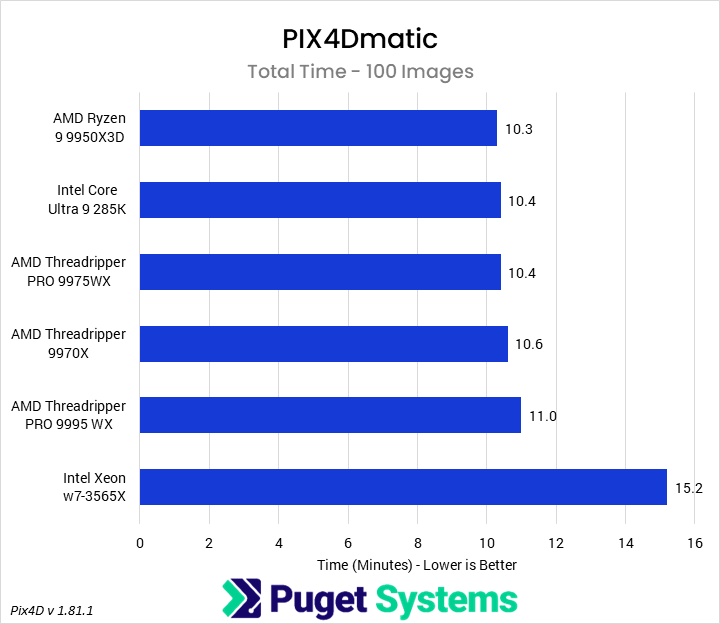

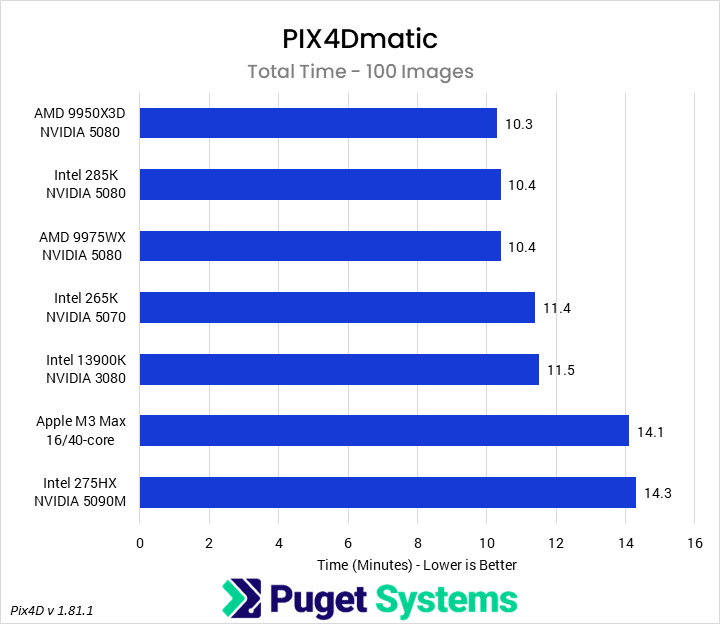

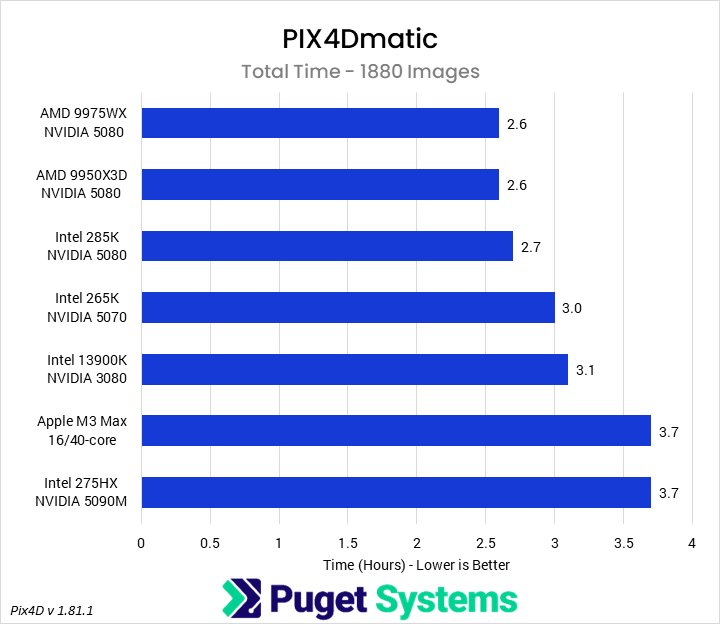

CPU

We started off looking at CPU results. PIX4Dmatic is an interesting program because of the mixture of workloads it uses during processing. Although some portions are fairly well threaded, we found areas like Calibration to be dependent on single-threaded CPU performance over multi-threaded performance. This meant that, for modern processors, the overall difference in time wasn’t huge. Processors with better single-threaded performance typically have worse multithreaded performance, and these tend to offset each other. Additionally, we found that the program didn’t use more than 64 logical processors, so scaling beyond 32 cores with SMT didn’t have any benefit.

It does appear that, as we increased the number of images, the relative performance between good single-threaded processors and good multi-threaded processors inverted, though the overall performance difference was still small. When we revisit PIX4Dmatic in the future with larger data sets, we suspect that may show more differentiation. Of course, there is a lurking variable here of RAM capacity. The AMD Ryzen™ 9950X3D and Intel Core™ Ultra 285K only had 64 GB of RAM, compared to 128 GB on the other systems, and we found that the larger image set used up to approximately 80 GB of RAM. This could also be responsible for the performance inversion, and will be another aspect to test in the future.

Overall, with a modern CPU, we don’t think that small and medium-sized image sets need a particularly powerful processor. A good quality desktop-class CPU should be sufficient, though for the larger-sized datasets, users will want more than 64 GB of RAM. We would recommend against a Xeon W processor, though, as we found ours to have exceptionally bad performance in this workflow.

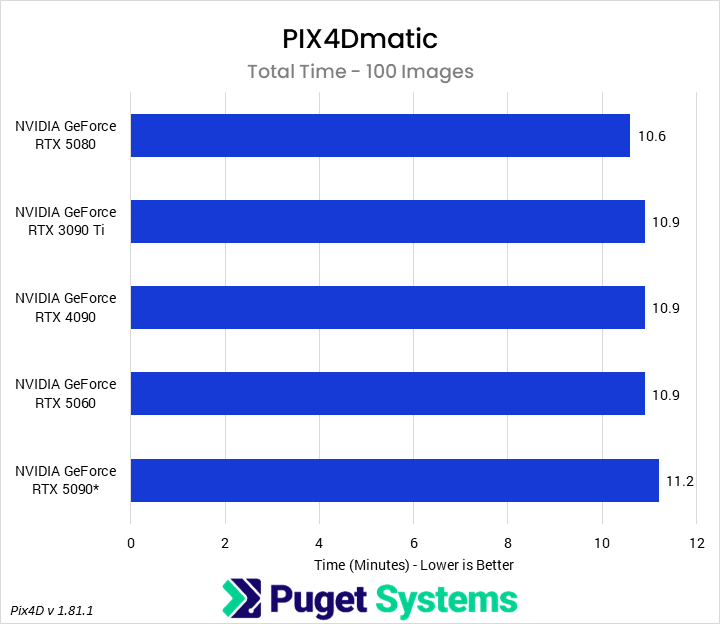

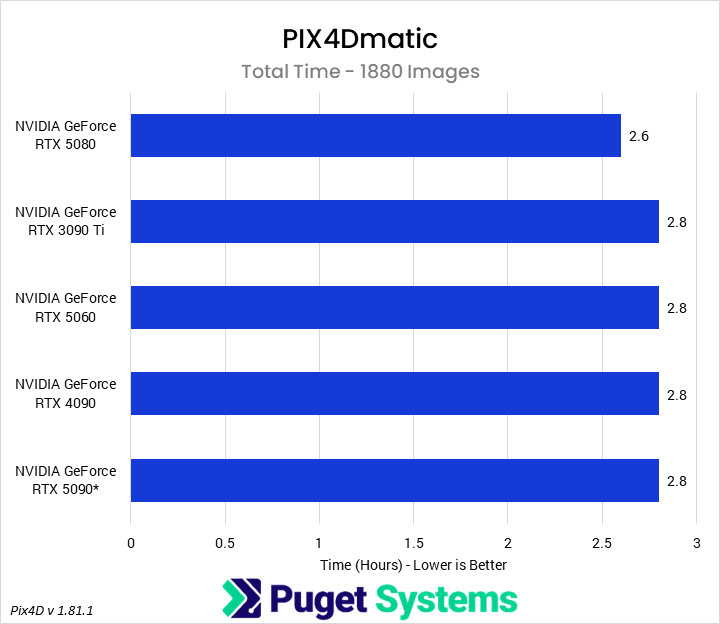

GPU

After CPUs, we examined whether GPUs have any effect on performance in PIX4Dmatic. Not all portions of the program are GPU-accelerated, but areas like Calibration, Dense point cloud, Image pre-processing, and Orthomosaic do make use of it. Interestingly, though, we didn’t see much difference in overall time between different GPUs. There was some benefit from a faster GPU, especially in the aforementioned areas, but investing in a high-end GPU probably isn’t necessary. We also found that the GeForce RTX 5090 performed anomalously badly in our testing, but we are not sure why this was the case.

The other aspect of GPU performance is VRAM capacity. In our testing, we observed that the 100-image dataset would use about 4 GB of VRAM, while the 1880-image dataset would use about 8 GB. This isn’t linear growth, but we expect that an image set on the scale of tens of thousands of images may want more than what some low-end cards provide. For most users, though, we’d stick with a modern NVIDIA GPU with at least 12 GB of VRAM.

System

Many PIX4Dmatic users are on older hardware or laptops. Although we didn’t have time to test too far into the past, we wanted to look at how some possible systems from a few years ago compare to modern configurations. The most interesting thing we found is that there is far more differentiation in performance between current and past-gen hardware than between different models within the same generation. For instance, a Core Ultra 9 285K paired with the GeForce RTX 5080 is 15% faster than a Core i9 13900K with RTX 3080.

Users on a laptop—especially an older laptop—would see fairly large improvements from moving to even a midrange desktop system. For example, a Core Ultra 7 265K paired with an RTX 5070 could reduce times by 20% from a top-end laptop. This represents a potential time savings of close to an hour on a multi-thousand-image dataset!

Conclusion

Overall, we found that high-end, enthusiast-class hardware was sufficient for maximizing performance in PIX4Dmatic at the dataset sizes we tested. A Ryzen 9 9950X3D, Core Ultra 9 285K, and all varieties of Threadripper 9000 processors performed nearly identically. We think it is possible we could see more differentiation here with a larger image set—something we hope to test in the future—but most end users don’t need to break the bank on super-high-end setups. Given that we didn’t see core usage beyond 64 logical processors, users don’t need to invest in the very highest-end Threadripper processors.

However, when comparing to lower-end or older systems, we found there were potentially significant time savings to be gained from better hardware. Going from a Core Ultra 7 265K and RTX 5070 to a 285K and 5080 could save 20 minutes on a three-hour processing step (a roughly 10% improvement). Going from laptop to desktop hardware was even more dramatic, with a high-end Windows laptop taking an hour longer than a comparable desktop computer on a nominal 2.7-hour-long render.

Based on our testing here, we found relatively consistent scaling between components across data set sizes. This means that on even larger datasets, we expect to see similar scaling. Given this, our general recommendation for desktop hardware is that an entry-level system should have a 265K or equivalent, 64 GB of RAM, and a NVIDIA GeForce RTX 50 Series card with at least 12 GB of VRAM. A mid-tier system, good for thousands of photographs, should feature a 9950X, 128 GB of RAM, and a 5080, while a top-end system wants a 9975WX with at least 256 GB of RAM and a 5080 or better.

Going forward, we plan on including PIX4Dmatic as part of our regular testing—both roundups on significant releases and as part of our AEC articles. This will allow us to cover even more hardware and ensure that there is good information for the best hardware to use for a PIX4Dmatic workstation.

If you need a powerful workstation to tackle the applications we’ve tested, the Puget Systems workstations on our solutions page are tailored to excel in various software packages. If you prefer a more hands-on approach, our custom configuration page helps you configure a workstation that matches your needs. Otherwise, if you would like more guidance in configuring a workstation that aligns with your unique workflow, our knowledgeable technology consultants are here to lend their expertise.